Our final 12th grade physics block, Visual Physics, ends up being as much a course in philosophy of science as a study of optics. A favorite experience is when we take a hose with a spray-nozzle, go outside on a sunny morning, make rainbows, and discover they transcend the idea of distance.

If you try this yourself, and orient just so, you’ll actually see not one but two rainbows: the bright, primary rainbow going from violet inside to red outside, and the larger, secondary rainbow outside, which is dimmer, broader, and with inverted color order. The double rainbow is its own mystery; but regardless of the number of rainbow echos, there are some patterns and ideas that hold true about all rainbows under all conditions.

We can begin by noting what conditions must exist in order to see any rainbow. They include:

- a self-illuminating image like the sun

- you: with a functional visual system

- a mist of some sort, not necessarily rain

- an orientation facing away from the illumination and toward the mist

- a dark enough backdrop contrast to see the rainbow colors well

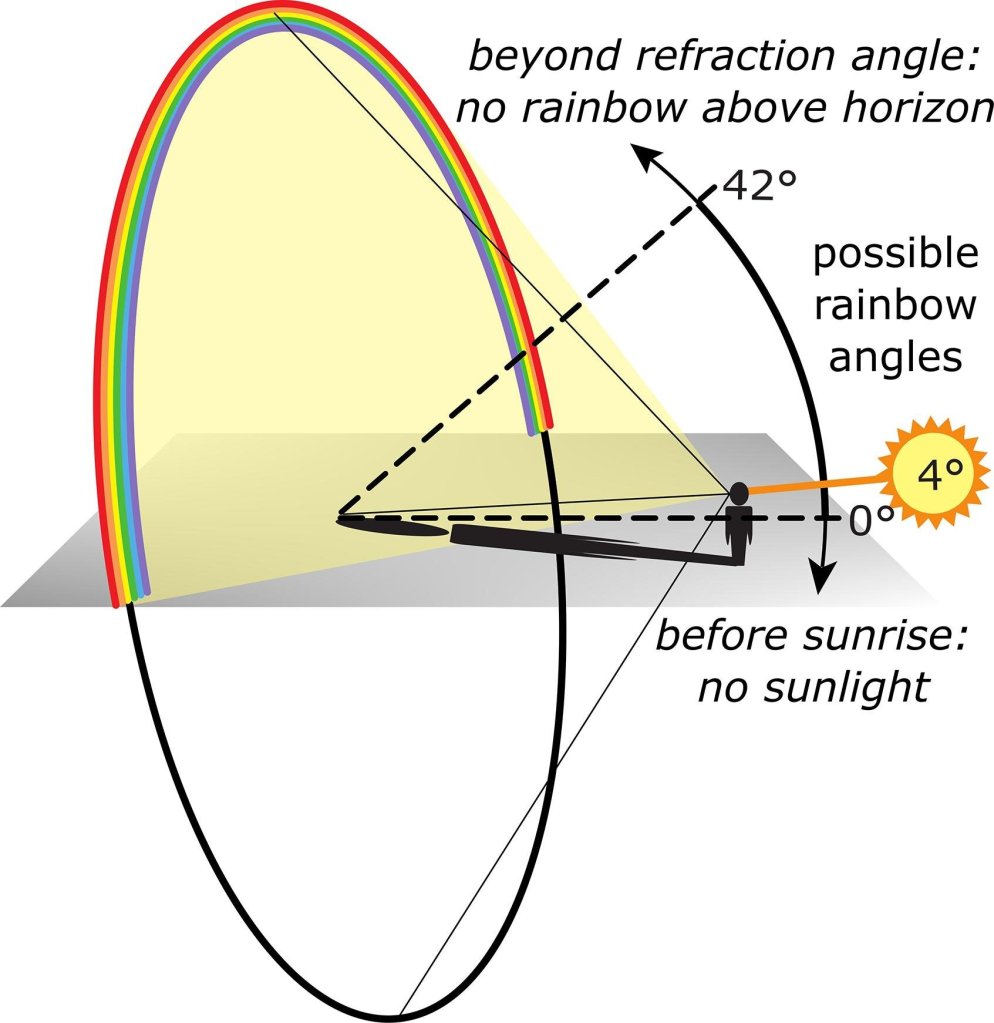

As the diagram depicts, no matter how far the mist is from you (as long as there is mist enough), all primary rainbows appear to all observers as (usually partial) circles of prismatic colors at about 42° from a center point that lies collinear with the sun and your third eye. If you move left or right, the rainbow moves with you. Its center is always on a straight line drawn from the sun through the back of your head.

If the sun is lying just on the horizon, and you are standing at ground level, the center of the rainbow is at the horizon too, and you will see exactly a half rainbow. If the sun sets, obviously, no rainbow. But also, once the sun rises above 42°: also no rainbow, unless there’s mist by your feet. This is why there aren’t many rainbows near the equator.

Now, with these facts on hand, let’s get to the crux of the philosophical argument. First: how far away is a rainbow from you? Is it infinitely far away? It moves with you, just like a countryside moves with you as you speed by on a train, or like the fixed stars move with you at night. Far away things move with us, whereas close things move quickly past us. On this basis, it would seem a rainbow’s location in space is infinitely far from us.

But wait. The mist is at a certain distance from us: does the rainbow not exist ‘on’ the droplets of mist? Without the mist, there’s no rainbow. That is causally true. Yet the mist might be ten feet, a mile, a hundred miles from us. Does the mist’s distance from us change the size or quality of the rainbow? No, not one bit. Yet, if we remove the mist anywhere on that 42° ring, no rainbow is seen in that part of the circle (that’s where you can usually find leprechauns, on a good day). So the mist’s angular location to the center of the rainbow matters, but not its distance from us.

That you need to have mist present in order to see a rainbow is not much of a reason for saying that the distance-location of the rainbow is ‘on the droplets.’ Because, by the same argument, we could equally say you need your eyes in order to see a rainbow: would the rainbow therefore exist on the surface of your eyeballs? On your retina? The middle of your head? No. But then where does the rainbow image actually exist? Not at any particular distance from you. It’s just… here.

The fact is, the concept of ‘distance from you’ is not applicable. It’s N/A. Rainbow have no distance-location from you. They only have an angular orientation relative to you and the sun. They move as if infinitely far away, but are not at any location we can call infinitely far away. All we can speak of is their relative-angular-location. A rainbow is ‘here’, as an intangible image, which, while not ‘attached to matter’, is nevertheless as real as any other perception. It is not an illusion. It is just much more obviously non-physical than other images are.

Now, here’s the sinker: if it is true that rainbows are ‘nowhere away’ from us, what prevents us from making the same claim about every image we see? Truly, the only difference is that we associate most images with the concept of the objects and substances that we imagine them being a part of. However, in actuality, all images are like rainbows: images are just here, at no tangible distance from us. We say ‘that desk is ten feet away’ because of the additional experience of being able to walk over to it, measure our steps, and touch the desk. But the image of the desk is just here, now. When we arrive at the desk, the image of it in that orientation is also just here for us. All images, in fact, live outside the concept of distance! Rainbows just show this fact to us most clearly, because they appear most dissociated from matter.

In short: distance is a concept, not a perception. And the concept of distance only has relative significance for certain parts of reality. It doesn’t apply to rainbows… or actually to any stand-alone visual experience. Visual reality transcends the third dimension. We might say that rainbows transcend spacetime.

These are the kinds of serious, playful conversations I have with 12th graders. By honing in on the simple example of a rainbow, and activating objective, imaginative capacities, we are able to draw out subtle ideas which lie nestled within all image phenomena, waiting to be realized by engaged human beings.

Leave a comment